THE PARADOXICAL PALM SUNDAY

- Charles

- 23 mars 2024

- 4 min de lecture

Reflections for the Palm Sunday of the Lord’s Passion: Isaiah 50:4-7; Philippians 2:6-1; Mark 14:1—15:47

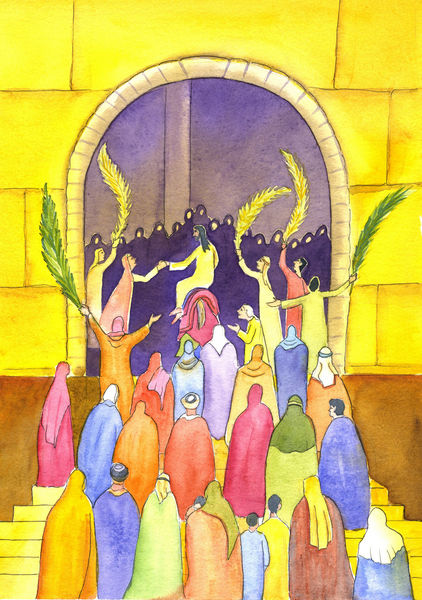

Jesus reaches the gates of Jerusalem, ready to ‘freely and willingly’ enter the Passion Week. Every city and village traversed thus far, every miracle and teaching accomplished, and every person met and transformed along the way have led him to this pivotal moment. This ‘triumphant’ entry is marked by a series of paradoxes and enigmas.

1. The City:

Despite their pronounced differences, all four gospels agree that the crossing of Jericho and the entry into Jerusalem city mark the beginning of the last phase of Jesus’ journey on earth. What makes this entrance remarkable is the symbolism of the city and the one entering it. Bethany and Bethphage are the last few villages that he visits before stopping on the Mount of Olives, for as Zechariah prophesied, “It is on this hill that God will set his feet at the end of time” (Zech 14:4). With this entry into Jerusalem, salvation history reaches a qualitatively new phase. The messiah enters his city as promised in Zechariah 9:9. The Shekinah glory that left the city (Ezekiel 10:18) returns in flesh and blood as foretold (Ezekiel 43:1-4; Isaiah 60:19; Revelation 15:8).

The paradox of the city, however, is the counter-movement that it initiates in response to the return of its King and shekinah glory. Two seemingly opposite processions are at work in the city: Jesus’ triumphal entry ‘into the walls of the city’ and his forced exit (in a few days) to Golgotha located ‘outside the walls of the city’. While God wishes to make an entrance, the city seems to resist. Fittingly, therefore, Luke records the moving episode of Jesus weeping over the city immediately after his entry. We read, “As he came near and saw the city, he wept over it, saying, “If you, even you, had only recognized on this day the things that make for peace! But now they are hidden from your eyes” (Luke 19:41-42). Jesus is the “meek and humble” messiah who offers himself to the city's welcome or rejection.

2. The Crowds:

Jesus is welcomed by a large crowd (Matthew and Mark) or a very great multitude (Matthew & John). The context is perhaps the Feast of Tabernacles/Sukkot, marked by the expectation of the coming of the Messiah. Waving the ritual branches (Leviticus 23:40), the pilgrims sang Psalm 118, “Hosanna (save therefore)! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!”. We sense a certain contrast between the local villagers, who acclaim him as the Christ and spread their cloaks on the road, and the townspeople (people of the city) who see him only as a trouble-making Galilean. However, this jubilant ambience of Palm Sunday will soon turn into the hostile/toxic environment of Good Friday. Chants of hosanna will soon turn into cries of “Crucify him”.

Why this sudden change? The crowd’s reception of the messiah was loaded with varied expectations. They wanted a liberator who would slay their enemies, abolish taxes, cleanse their soil of ‘all pagan impurity’, and fulfil the centuries-old dream of the new Israel. While this logic of receiving animates the crowd, Jesus proposes the alternative logic of kenosis (complete self-giving). He shifts the focus from receiving to giving. He knows the price of salvation that he needs to pay but he also challenges his people to participate in his sacrifice. His passion is the door to love and self-giving. His life, voluntarily given the following Friday, is the door to love and self-giving. “It is more blessed to give than to receive” (Acts 20:35). Our palms and hosannas should make us partners in the struggle for peace, justice, and liberation following in the footsteps of Jesus, King of Peace, humble and compassionate Messiah. We don’t just stand on the sidewalk, we walk the way of the cross in our own history and fragility.

3. The Christ:

Prophets, Scripture scholars and religious leaders of Jesus’ time were expecting a great champion, a Davidic Messiah, who would come with a mighty army to crush the Romans and restore the kingdom of Israel. They have kept this hope alive for centuries despite their sufferings, hardships and gleaming impossibilities. And now when the moment is here, the Messiah enters his city mounted on a colt. While everyone is waiting for a true warrior king, strong, brave, and cruel to his adversaries, Jesus arrives not as the victor but as the victim (first reading). Confronted with this paradox, his contemporaries ask “Who is this man?”: A prophet? More than a prophet? Messiah? Son of David? Or just the son of a carpenter? An obnoxious Galilean blasphemer? Christ’s entry into Jerusalem challenges our predefined suppositions, narrow expectations, and self-centred spiritualities.

The Palm Sunday King wants us to enter the paradox of a fragile God, who riding on a colt, returns to his city with the mission of salvation, offering himself as a victim to be ridiculed, mocked at, spat upon, scourged, crucified, murdered, and buried. He requires us to open our eyes of faith, acclaim our King, and allow this paradoxical Messiah to enter the most secret depths of our lives. Christ, the all-powerful yet powerless, absolute yet immanent, victor cum victim wishes to be welcomed for what he is and not for what we want him to be. God’s subversive Good News begins from a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes; continues in Jesus’ ministry for the least, the lost and the unwell; progresses in accepting the death of a criminal on the cross and reaches its climax in the Resurrection. From the crib to the cross and the cave, God poses before us a taunt, a challenge, turning upside down our expectations and our ideologies. It is with our eyes of faith that we grasp his presence, precisely when voices around seem to cry that he is not here, that he is absent, that he has abandoned us to our fate.

May our entry into the Holy Week help us respond to Christ’s entry with enthusiasm, enter the logic of kenosis (giving), and recognise his true identity with the eyes of faith.

Commentaires